Ted Smyth

U.S. Support for Ireland Should Not Be taken for Granted

By Ted Smyth

A Newsletter, January 7, 2023

President Bill Clinton with SDLP Leader John Hume in 1995.

Photo: Sharon Farmer and White House Photograph Office.

Sometimes Irish people seem to take the resolute support for Ireland from President Biden and the US Congress for granted as if it is the natural order. For a small nation, Ireland enjoys privileged access to power in Washington essentially because of the exeptional commitment of both powerful and ordinary Irish Americans to their heritage and to alignment on key policies.

However, for many of the first 100 years of independence Ireland did not have a strong relationship with Washington. Up to the 1970s the US government consistently sided with the British government on Nothern Ireland policy, declaring it an internal British matter. Indeed, as far back as 1919, President Wilson even refused to support self-government for Ireland at the Paris Peace Conference despite intensive lobbying from Irish America.

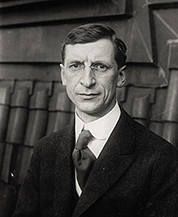

Éamon de Valera .Photo: National Photo Company Collection, WikipediaWhile the US was one of the first countries to establish diplomatic relations with the Irish State, Washington prioritized its relations with the British government, its ally in the First World War, and a global military ally for many years against fascism and communism.

Any hope of strengthening Ireland’s relationship with Washington dimmed in 1941 when Mr. de Valera’s government refused to join with the United States in its extended war against fascist Germany. That Irish bitterness against the British could overcome its repugnance for Adolf Hitler stunned Americans. American and Irish American servicemen found it hard to accept that Irish neutrality was more important than providing the United States with military bases in the South to protect their sailors and troopships on the Atlantic crossing to Europe.

Ireland exacerbated the rift with Washington in 1949 when it made ending partition a condition of joining the NATO pact against communism and Soviet aggression, again prioritizing antipathy for British rule in the North over a stronger relationship with the United States.

President John Kennedy in Ireland in 1963 JFK and family members in Ireland in June 1963.

Photo: JFK Presidential LibraryPresident Kennedy made a celebrated visit to Ireland in 1963, no doubt with a nod to the Irish American vote the following year. That visit improved relations between the two countries, leading to growing tourism and investment from America. In a speech to Dail Eireann, Kennedy praised Ireland’s role in the world but studiously avoided supporting the anti-partition position of the Dublin government.

Ten years later, American policy on Northern Ireland changed significantly to one of constructive engagement with Dublin prompted by a number of developments, including the angry reaction of Irish Americans to the brutal television images of British soldiers shooting civil rights marchers in Derry. Irish American leaders persuaded the US Senate to hold hearings on the killings which attracted widespread media coverage and influenced London to suspend the Stormont government.

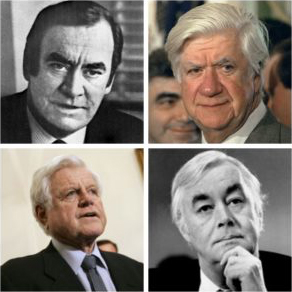

The Four Horsemen (clockwise): Hugh Carey, Tip O’Neill, Pat Moynihan and Ted Kennedy.What particularly shifted Washington’s approach to Northern Ireland was when Irish politicians changed their policy from calling for an end to partition to one of supporting equality for nationalists and unionists in the North. John Hume and Irish diplomats secured the support for this policy from the so-called Four Horsemen – Speaker Tip O’Neill, Senators Ted Kennedy, Pat Moynihan, and Governor Hugh Carey – and these powerful Irish Americans sold it to successive US Presidents.

The result was that at least four times since 1977, the positive pressure from American presidents for peace and equal rights in Northern Ireland has proven crucial to the peace process, persuading dilatory or hostile British governments to adopt a policy favoring equality between unionists and nationalists.

First, President Carter announced, despite British government and State Department opposition, that “the United States wholeheartedly supports peaceful means for finding a just solution that involves both parts of the community of Northern Ireland .and protects human rights and guarantees freedom from discrimination–a solution that the people in Northern Ireland, as well as the Governments of Great Britain and Ireland, can support.”

This was the first time ever that a US government supported the role of the Irish government in a solution to the Northern Ireland conflict.

Eight years later in 1985, when Prime Minister Thatcher was refusing to sign the Anglo-Irish Agreement, President Reagan, at the instigation of Speaker Tip O’Neill, persuaded Thatcher to sign that crucial stepping stone to the Good Friday/Belfast Agreement.

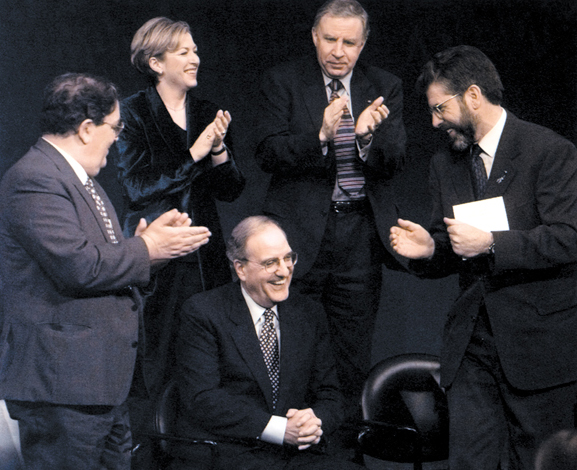

Next, President Clinton and his Special Envoy, Senator Mitchell played an indispensable role in the negotiation of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

Dec. 7, 1998: George Mitchell is applauded by fellow recipients of the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award. John Hume, left, and Gerry Adams, right, during a ceremony in Boston. Also pictured are Liz O’Donnell, Ireland’s Minister of State, and Paul Murphy, N. Ireland’s Minister of state. Eight Northern Ireland political leaders and Mitchell were honored for their part in the Good Friday Agreement.

Joe Biden in Carlingford, Co Louth, June 25, 2016. Photo: ROLLINGNEWS.IEt

And today, President Biden, a US President who genuinely loves his Irish heritage, has stressed to three British Prime Ministers what he termed in March 2022, his “deep commitment to protecting the hard-won gains of peace in Northern Ireland.” He stated clearly that “the Good Friday Agreement has been the foundation of peace and prosperity in Northern Ireland for nearly 25 years, and it cannot change.”President Biden, who has called for London and Brussels to find a solution to the Northern Ireland Protocol that protects peace in Ireland, also supports the bipartisan determination of Congress to delay a US-UK trade agreement as long as the Good Friday Agreement is threatened.

This extraordinary record of support by successive American presidents reflects America’s interest in preventing instability in Ireland, but it also reflects the love for their Irish heritage by American leaders of Irish descent and the importance of being responsive to Irish American voters.

Thanks to Irish organizations such as the Ireland Funds, the bipartisan Committee to Protect the Good Friday Agreement, and Irish studies centres like those at Glucksman Ireland House NYU, Boston College, and Georgetown, Irish Americans are more informed about the complexity of Northern Ireland and the need to accommodate both Irish and British identities in any future relationship.

Granting the right to vote in Irish Presidential elections to Irish citizens living outside the State would deepen that constructive engagement by Irish America, particularly amongst the Next Generation that must be cultivated.

Going forward, what role is the US government likely to play in the future of Ireland? It is hardly a secret that President Biden would like to visit Ireland to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement next April, but much will depend on the political will and ability of Prime Minister Sunak to negotiate a solution with Brussels on the Protocol that encourages the Northern Ireland Assembly to go back to work.

Joseph Patrick Kennedy IIIPresident Biden demonstrated his “continued, steadfast support” for the Belfast Agreement and his wish to cooperate with both communities in the North by his recent appointment of former Congressman Joe Kennedy III as US Special Envoy to Northern Ireland with a mandate to support its economic growth, including encouraging US business to invest in the North. The President’s Administration, whose National Security Council is one of the most experienced ever on Irish matters – including Director Jake Sullivan, Amanda Sloat, and Tom Wright – will likely urge caution in any rush to a dual referendum on Irish unity unless it convincingly accommodates both the British and Irish identities.

With President Biden expected to run again in 2024, one thing is certain, the Irish search for an agreed Ireland will continue to have a firm friend in the White House.

Editor’s Note: US Support for Ireland Should Not Be taken for Granted first appeared as an OpEd piece in The Irish Times on January 3, 2023, by Ted Smyth, President Advisory Board Glucksman Ireland House for Irish Studies NYU.

Pete Hamill at the Glucksman Ireland House NYU Annual Gala 2015, February 24, 2015.

Photo: James Higgins © 2015By Ted Smyth

August 7, 2020Three years ago, I read Pete Hamill’s essay, “Notes for the New Irish: A Guide for the Goyim,” in New York magazine’s special Irish Edition in March 1972. What a revelation that turned out to be. Lurking behind the cover of a vivid, burning green Irish harp, between ads for Benson and Hedges and Sony stereos, Pete wrote one of the best descriptions ever of the changing nature of Irish identity in America. Jack Deacy, then a 27-year-old hell-raiser fresh back from Belfast, had successfully convinced editor Clay Felker that if the Chinese could have a special edition, so could the Irish. Gail Sheehy wrote a vivid account of the “Fighting Women of Ireland” from Belfast, Dennis Duggan profiled Judge Comerford, and Joe Flaherty rightly observed that ’The Irish mess’ is not due to some genetic defect in the Irish character. It is, to be accurate, a British mess.” (My thanks to Professor Marion Casey at Glucksman Ireland House NYU for suggesting I read the special edition.)

In his article, Pete concluded that the conflict in Northern Ireland and the Bloody Sunday killings by British paratroops of 13 unarmed civil rights marchers in Derry a few weeks earlier in January 1972, had been a watershed moment for Irish America: “Something exhilarating has happened to the Irish this past year, the reforging of a lost cultural identity. Suddenly, younger Americans became interested in their Irish identity, the formation of “the New Irish who had moved on. They were largely people of the Left because they had read Irish history and been formed by Jewish thought. They came out of the Army and went into Vietnam Veterans Against the War instead of the American Legion.” Tom Hayden, in his book, Irish on the Inside: In Search of the Soul of Irish America, echoed this in writing that he first realized he was “Irish on the inside” when he heard civil rights marchers in Northern Ireland singing “we shall overcome.”

But everyone should read Pete’s New York magazine article in its entirety for the sheer bloody exuberance of Pete’s prose, his close observation, original mind, sense of history and community and his compassion for working people. Leading off from an Irish gathering in the McFadden Brothers Post of the American Legion, Pete reflected on the glory that had been lost: “Once the Irish ran New York; they were the bone and muscle of political power in every borough…But slowly, almost imperceptibly, their world had changed; sons came home from the Army, married their old girlfriends and rushed to the suburbs: continuity was broken, the old lines of familial authority and neighborhood loyalty were frayed and then seemed to vanish; the Church dried up in the dusty hands of Pacelli, had one rush of movement under Roncalli, and then seemed to die again, leaving some sense of ritual lost, some magical sense of wonder evaporated.”

Pete Hamill at the Glucksman Ireland House NYU Annual Gala 2015, February 24, 2015.

Photo: James Higgins © 2015What a gripping description of the Catholic Church losing its hold on the Irish in the mid-twentieth century! And then this, on the ambitions of the Irish before they became leaders in every sector of today’s America: “An entire generation of young Irish Americans went through Brooklyn Prep, Regis, Xavier, Cardinal Hayes and other high schools convinced that their highest ambition in life would be to join the priesthood or its lay affiliates, the FBI, the CIA and IBM.”

Pete rightly gave credit to the Kennedys, the Berrigan brothers, Irish nuns and Paul O’Dwyer for standing up for racial equality and civil rights for Black Americans in the 1960s: “It was Paul O’Dwyer who kept the capacity of political faith alive during those years… he kept alive notions of political justice and idealism that had always marked the best Irish in Ireland.” We are fortunate that Paul’s son, Brian O’Dwyer, has carried on the family tradition, campaigning relentlessly for racial equality and comprehensive immigration reform.

Pete Hamill was one of the few who could be as eloquent in speech as he was inspiring in his prose; we will miss him terribly, but we are so grateful that his words live on to inspire and enrich future generations. Thank goodness two years ago, Loretta Brennan Glucksman, the founder of Glucksman Ireland House, proposed we celebrate our fellow Board Member, the indomitable Pete; it was a magical evening as we relished the eloquence, humor and originality of that lovely man who is now gone.

Loretta speaks for all of us when she says, “Pete Hamill, my hero, was not only a gifted writer, but one of the best human beings ever. A valued Board Member of Glucksman Ireland House, NYU, Pete was always so generous to young scholars, writers and journalists, inspiring them to leave the world a better place than what they found it, as he surely did. Pete and Fukiko were among my closest friends and I will miss him dearly.”

Tribute to Pete Hamill at Glucksman Ireland House December 10, 2018 on Youtube and the Pete Hamill tribute page.